Introduction

Amines are our functional group guest today—and they’re definitely the eccentric ones. They behave like that slightly awkward, joke-cracking friend who might seem like a sociopath, but without them, the group dynamic and the whole event just wouldn’t be as exciting. I use this labeling because this functional group is the absolute key to the odor profiles of several heavy-hitting molecules—the ones that give us the scents of jasmine, coffee, chocolate, burnt nuts, bread crust, popcorn, naphthalene, neroli, wet earth, fecal, and leather. If that doesn’t sound crazy enough, consider this: the pleasant qualities of your gourmand, jasmine, woody, leathery, or neroli scents wouldn’t be possible without amines and the unique aromas they contribute. Let’s just get into the lab and learn more about amines.

Table of Contents

Structural Fundamentals of Amines in Organic Chemistry

In organic chemistry, we define amines as molecules where a nitrogen atom is bonded directly to a carbon atom (C-N). Simple rule for the lab: if you see that carbon-nitrogen bond, you’re probanly looking at an amine.

Think of these compounds as derivatives of ammonia (NH3). You create them by swapping out one or more of ammonia’s hydrogen atoms for hydrocarbon groups. Now, everyone knows ammonia—it’s that sharp, intense smell that hits you like the smelling salts bodybuilders use to get hyped before a lift. It’s the kind of odor that makes your head snap back involuntarily. That shared intensity is the dead giveaway of the chemical connection here; it’s a real “chip off the old block” situation.

But here is what really sets amines apart from everything else on your bench: that unbonded lone pair of electrons sitting on the nitrogen. That free lone pair is the driver. It dictates almost every important physical characteristic of these molecules, making them totally unique compared to the other compounds we work with.

Atomic Configuration and Hybridization

The nitrogen atom in your amines is typically sp3 hybridized, but because of that lone pair of electrons I keep mentioning, this sp3 structure is a different beast compared to typical carbon sp3 hybridization.

Think of that lone pair as a space-hog—it takes up more room than a standard bond and pushes the carbons away from it. Because of that “bullying” effect, the bond angle is slightly tighter than the ideal trigonal pyramidal structure you see in basic chemistry books.

The reason I’ve been hammering on about this lone pair isn’t because it’s some useless part of the molecule; it’s actually a high-energy power-player. That pair of electrons is hungry—it’s capable of snatching up positively charged hydrogens (or protons, to be exact; remember, if you strip the single electron off a hydrogen, you’re left with just a free proton) to form an ammonium ion.

This is a massive deal for us in the lab. It means that in an acidic environment, your amines will undergo a reaction and transform into ammonium ions. Once that happens, the structure flips, and your odor characteristics are going to change completely. You aren’t smelling the same material anymore.

Classification by Substitution

Amines can hang up to three alkyl or aryl groups off that central nitrogen at the same time. This variety is why we have to classify them properly. Here’s the rule: unlike alcohols—which we classify based on the carbon atom they’re stuck to—we classify amines based on how many carbons are directly bonded to the nitrogen.

Here is the breakdown you need to memorize:

- Primary Amines (1°): The nitrogen is bonded to just one alkyl or aryl group and two hydrogens.

- Secondary Amines (2°): Two groups are bonded to the nitrogen, leaving only one hydrogen.

- Tertiary Amines (3°): All three hydrogens are gone, replaced by three alkyl or aryl groups.

- Quaternary Ammonium (4°): You probably won’t see these in your fragrance formulas. In this class, even that lone pair of electrons I keep talking about is replaced by a fourth group. This gives the nitrogen four bonds and a positive charge. You’ll find these in conditioners and surfactants, but they aren’t the stars of our scent profiles.

The “Why”: Tenacity and Volatility

Why do I care if you know these classes? Because of physics.

In primary and secondary amines, the nitrogen is still holding onto at least one hydrogen. That means these molecules can form hydrogen bonds with each other. They “stick” together. Because of that attraction, it’s harder to pull them apart—meaning they don’t evaporate as easily.

If you compare a primary amine to a tertiary amine with the same molecular weight, the primary one is going to stay on the blotter longer. The tertiary amine has no N-H bonds, so it can’t “stick” to its neighbors the same way.

Etymological Origins

It’s pretty easy to spot that the word “amine” is just “ammonia” with the suffix “-ine” tacked on. Back in the late 19th century, when the pioneers of organic chemistry were finally getting things organized, they used “amine” to define any substance where a hydrocarbon radical (like an alkyl or aryl group) swapped places with a hydrogen atom in ammonia.

But where does the word “ammonia” even come from?

A Swedish chemist named Torbern Bergman came up with it in 1782. He pulled it from scientific Latin to describe the gas released by “sal ammoniac”—or ammonium chloride, to the rest of us. The name actually traces back to mineral deposits found near the Temple of Jupiter Ammon in Libya.

Here’s the fun part: those salts were essentially formed from the sand where camels spent their time while their owners were praying. That’s how we first started clueing in on nitrogen compounds. Before we got technical, people were calling these things volatile “animal alkalis” or even “spirits of hartshorn.” It’s a dirty origin for such a clean science, but that’s history for you.

Evolution of Chemical Terminology

The way we name these things has shifted over time, especially as we’ve uncovered more nitrogen-heavy materials. Take Aniline, for instance. It’s an absolute staple—a heavyweight aromatic amine used in everything from industrial dyes to high-end perfumery. Back in 1841, a German chemist named Carl Julius Fritzsche coined the name, pulling it from the Portuguese word “anil,” which means indigo.

Another neat example is the word “vitamin,” which shows just how deeply amines are tied into the essentials of life. Casimir Funk first called them “vitamines” back in 1912 because, at the time, the consensus was that these nutrients had to contain amino groups to be vital for survival. We eventually dropped that “e” once we realized not all vitamins were actually amines, but the history is right there in the name. This whole backstory just goes to show how central amines have been to pushing the boundaries of both chemistry and biology.

Systematic Nomenclature of Amines in Perfumery

Look, we aren’t going to sit here and grind through a boring review of systematic naming rules. Why? Because in the fragrance industry, amines always have their own special names. You’re probably never going to see a standard IUPAC name on a real-world formula in this lab. For those who actually wonder about the technical side of things, I’ll leave a link in the sources.

The Olfactory Profile of Amines

As we discussed at the start, amines have a very strange—maybe even creepy—scent palette. Most of the time, in high concentrations, they smell objectively bad. But the low-concentration range is the area where the really interesting changes occur.

Let’s divide these into groups based on how they actually hit the nose:

- Anthranilates: Methyl anthranilate (and dimethyl anthranilate before it got the ban) is a powerhouse molecule. It has a narcotic, floral, slightly citrus-blossom scent that shows up naturally in jasmine absolute, neroli, and ylang-ylang oils. It’s that deep, heavy floral note that feels almost intoxicating.

- Indole and Skatole (3-methylindole): Okay, let’s be real: in big doses, these two smell totally fecal. Indole is actually found in jasmine naturally, and when you dilute it, it’s the key to building those realistic, lovely jasmine notes. Then you have Skatole—the “Fecal King.” But don’t let the name fool you; it’s incredibly valuable, especially for whipping up authentic oud and leather accords. It gives them that animalic character you can’t get anywhere else.

- Pyrazines: Most pyrazines hit you with a profile that smells like cacao or roasted nuts. We use these primarily in gourmand smells where you need that toasted, “brown” aromatic quality.

- Quinolines: This group has a very distinct scent of leather, wet earth, and a bit of a galbanum-like greenness. If you’re looking to build something earthy, sharp, or animalic-leathery, this is where you start.

Profiles of Key Nitrogen Compounds: The Heavy Hitters

Even though some of these are technically esters, it’s the nitrogen group that does the heavy lifting for their character. Here are the specific materials you’ll be reaching for on the bench:

- Methyl Anthranilate (CAS No: 134-20-3) This stuff has a powerful, narcotic scent that immediately hits you with Concord grapes and orange blossoms. But look closer and you’ll notice a strange, medicinal naphthalene note—it smells exactly like an old closet. In the lab, this is your secret weapon for creating sweet, realistic white florals and those specific “grapey” fruit accords.

- Ethyl Anthranilate (CAS No: 87-25-2) Think of this as the smoother younger brother of Methyl Anthranilate. It offers a sweet, fruity aroma that’s very similar but feels much milder and less harsh on the nose. You get those classic grape and orange blossom notes, but with a bright hint of wintergreen mixed in. Use this when you want to add soft floral sweetness to citrus or starfruit compositions without the “bite.”

- Methyl N-methylanthranilate (CAS No: 85-91-6) Most of us just call this Dimethyl Anthranilate. It smells like ripe grapes and mandarin orange peels, with distinct winey and berry nuances that feel more refined and “citrus-floral” than the other anthranilates. The big win here is stability—it doesn’t discolor your juice as easily as the others when you start mixing in aldehydes.

- Indole (2,3-benzopyrolle) (CAS No: 120-72-9) This is a famous one. It smells intensely floral and animalic, acting as the “living” heart of natural jasmine and orange blossom. Now, everyone knows it’s famously fecal and repulsive when it’s concentrated, but it transforms into a beautiful erogenic warmth in trace amounts. It’s essential if you want to give a white floral perfume that realistic, “bloom-like” depth.

- Skatole (3-methylindole) (CAS No: 83-34-1) If you thought indole was intense, meet Skatole. It’s even more powerful, putrid, and distinctly fecal. But here’s the trick: once you dilute it to an extreme level, it takes on a warm, floral character reminiscent of natural jasmine. We use it very sparingly to add that “dirty” animalic realism to narcotic floral blends. If you want it to smell real, you usually have to get a little dirty.

- 6-Isobutylquinoline (IBQ) (CAS No: 6819-19-8) This is a legendary raw material. If you’ve ever smelled a high-end leather accord that felt truly authentic, IBQ was likely doing the heavy lifting. It’s got a complex, narcotic profile that blends earthy green roots with a specific roasted or even burnt quality. It’s absolutely indispensable when you’re building dark, sophisticated leathery or chypre accords that need to feel grounded and expensive.

- 6-Methylquinoline (CAS No: 91-62-3) This one is prized for its narcotic and earthy green odor—it feels deep and very grounded. In this lab, we use it almost exclusively for specialized tea-related formulations. It’s the secret to recreating that authentic, slightly savory scent of dried tea leaves. It adds a sophisticated “bitter-green” facet that pairs perfectly with herbal or woody notes.

- 2,6-Dimethylpyridine (CAS No: 108-48-5) Also known as 2,6-Lutidine, this material has a sharp, diffusive scent that can be a bit confusing at first. It transitions from minty to nutty and coffee-like depending on the concentration. When you use it in tiny amounts, it contributes bready, meaty, and cocoa nuances. It’s a powerful “brown” note that works wonders in roasted or savory olfactory profiles.

- 2-Acetylpyrazine (CAS No: 22047-25-2) This molecule is the hallmark scent of freshly popped popcorn and warm bread crust. It has an incredibly high odor impact, so be careful—it delivers toasted and nutty notes even in minute quantities. In gourmand perfumery, this is your go-to ingredient if you want to add a cozy, “just-baked” realism to a blend.

- 2-Methoxy-3-isobutylpyrazine (CAS No: 24683-00-9) This pyrazine provides that unmistakable, sharp scent of green bell peppers or freshly snapped peas. It is extremely potent—the human nose can detect this at levels as low as parts per trillion. You’ll primarily use this to add a crisp, earthy vegetable “snap” to green and galbanum-style accords. Just remember: a little goes a long way.

- 2,3,5,6-Tetramethylpyrazine (CAS No: 1124-11-4) Also known as Ligustrazine, this compound has a warm, toasted aroma that smells like roasted cocoa shells and nuts. It adds a malty, cereal-like depth that is perfect for building out chocolate, coffee, and other gourmand profiles. It provides a cozy, edible warmth that helps ground lighter floral or fruity notes.

- 2,3,5-Trimethylpyrazine (CAS No: 14667-55-1) This material delivers an intensely nutty and roasted character, with some surprising nuances of baked potato and hazelnut. It’s very powerful and requires heavy dilution to reveal its pleasant, biscuity warmth. It’s widely used to give a realistic “grilled” or toasted finish to complex gourmand and tobacco accords.

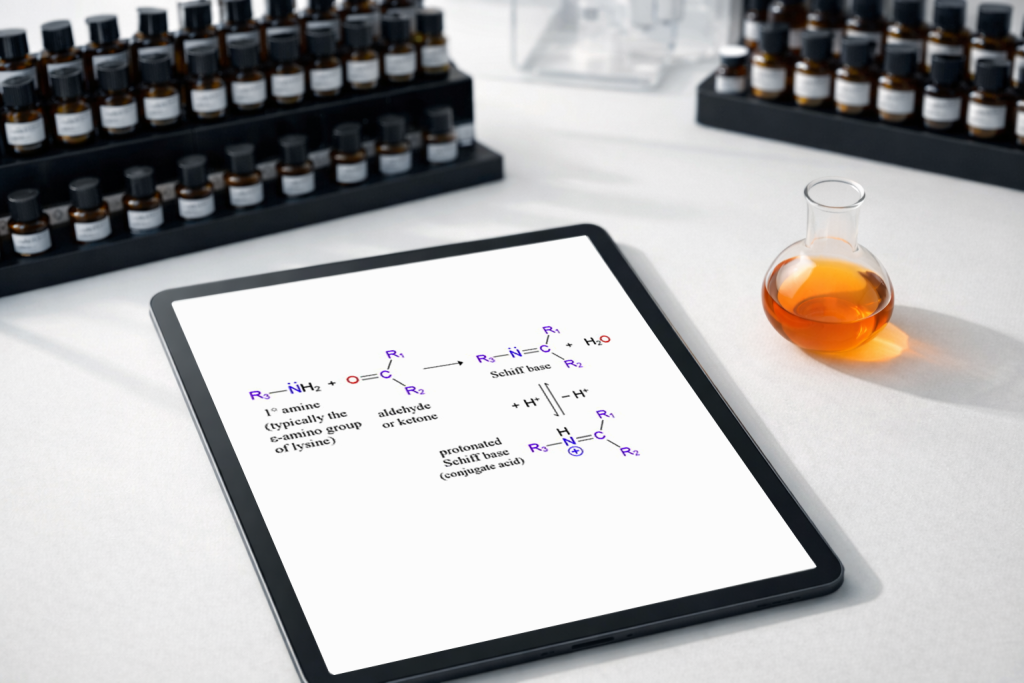

Schiff Bases

The single most important phenomenon you’ll deal with when working with amines in fragrance development is the formation of Schiff bases. This happens when a primary amine reacts with an aldehyde or a ketone.

In simple terms, they hook up to form a new, larger molecule and release a water molecule in the process. It’s a condensation reaction. But keep this in mind: the reaction is reversible. You can actually flip it back—essentially “re-releasing” the original materials—using heat or moisture.

Now, Schiff bases are a bit of a double-edged sword. If you form one accidentally, you’re looking at serious color changes that can ruin a product’s aesthetic. But when you use them intentionally? They offer levels of functionality that the original molecules just can’t touch on their own.

Here is why we use them:

- Tenacity and Volatility Schiff bases have a significantly higher molecular weight than the aldehydes they’re built from. In our world, heavier means slower. This makes them much less volatile and massively increases their tenacity—or longevity—on the skin or a smelling strip. Take Aurantiol, for example; it can hang around for over 300 hours. You won’t get that kind of performance from a standard aldehyde.

- Stability Aldehydes are notorious “divas” in the lab—they are incredibly prone to oxidation, which turns them into odorless, useless carboxylic acids. By reacting them with an amine to form a Schiff base, you’re essentially putting the aldehyde in a “protective cage.” It’s released slowly over time through hydrolysis, keeping the scent profile intact way longer than usual.

- Synergy The odor of a Schiff base is often a harmonious blend that is better than the sum of its parts. A classic example is reacting Methyl Anthranilate (that grape/orange blossom vibe) with Hydroxycitronellal (lily of the valley). The result is Aurantiol—a powerful, sweet, jasmine-like accord builder that brings a synergy you just can’t get by simply mixing the two materials in a beaker.

One of the absolute most famous Schiff bases is Aurantiol, which is formed through the reaction of Methyl Anthranilate and the aldehyde Hydroxycitronellal. This raw material has a very specific yellow color accompanied by a sweet, orange blossom-like scent. You’ve probably noticed that distinct, yellowish-orange color in fragrances with an orange blossom profile; that type of hue is generally the visual signature of a Schiff base.

Stability of Amines and Schiff Bases across Environments

The chemical stability of amines is a primary concern once your formula leaves the lab. Because of their basicity and high reactivity, these molecules behave differently depending on the pH, temperature, and light exposure of the final product. If you don’t account for this, your fragrance won’t survive on the shelf.

Behavior in pH Environments

- Alkaline Environments (pH 8-12): Amines generally feel right at home in alkaline conditions. In their “free base” form, they are stable and deliver their characteristic odor profiles. This makes them a solid fit for products like laundry detergents and bar soaps. Just keep an eye on the concentration—if the pH is too high, it can push the equilibrium so far that the free amine becomes overly volatile, potentially overpowering the rest of the fragrance with a sharp, fishy ammonia-like bite.

- Acidic Environments (pH < 4): This is where things get tricky. Remember that lone pair of electrons I mentioned? In an acidic environment, amines act as bases and “snatch” a proton (H+) from the acid. This turns the neutral amine into a positively charged ammonium salt.

Thermal Stability

In the lab, heat is our tool. Making Schiff bases usually requires some energy—we’re often cranking the temperature up to around 90°C to get that condensation reaction moving.

But outside of the synthesis phase, heat is usually the enemy. Leaving these materials in high heat for too long during storage is bad news; it can trigger a premature breakdown or kick off unwanted side-reactions.

It gets even more volatile in applications like candles. When a fragrance contains amines or Schiff bases, the intense heat of the flame (combustion) can actually tear the molecules apart. When that happens, you aren’t just losing the scent—you’re potentially creating nitrogen oxides and other volatile byproducts. That’s a surefire way to ruin the olfactory profile of a high-end candle and replace it with something sharp and industrial.

UV Exposure and Discoloration

One of the biggest headaches you’ll face with amines—especially the aromatic ones—is their tendency to discolor under UV light. It’s the primary reason some of the most beautiful fragrances on the market turn dark over time.

Materials like Methyl Anthranilate and its “buddies,” such as Indole, are incredibly light-sensitive. If your formula has a decent load of these, and it’s sitting in a clear bottle exposed to sunlight, you’re going to see a massive shift. We’re talking about your juice going from clear to deep yellow, orange, or even a muddy dark brown.

How They Change Color

The chemistry behind the shift is actually pretty fascinating. When Methyl Anthranilate forms a Schiff base, it essentially stretches out the molecule’s conjugated pi-electron system.

In technical terms, this creates a bathochromic shift (sometimes called a “red shift”) in its UV absorption. The molecule stops just absorbing invisible UV light and starts absorbing light in the visible spectrum. Once that happens, the material begins to look colored to the human eye.

To fight this, we don’t just hope for the best. Formulators typically have to toss in UV absorbers, like oxybenzone, directly into the perfume mix to intercept those rays before they can mess with the nitrogen chemistry.

Conclusion: The Indispensable Role of Nitrogen

Amines are absolutely key in modern perfumery, even if they can be a bit of a nightmare to manage on the bench.

Chemically speaking, they cover a massive range of smells. From the “super gross,” like the fecal punch of indole, to the intoxicating, gorgeous scent of a jasmine flower in full bloom—it just shows how wild and complex our sense of smell really is.

The cool part is how we use Schiff bases to cleverly manipulate the volatility of aldehydes and the reactivity of amines. This trick is how we build fragrances that last longer and have that rich, layered depth that keeps people coming back. Looking ahead, nitrogen chemistry is going to stay a major focus for innovation, especially as we push for greener synthesis and better delivery systems. The “scent and science” of amines isn’t going anywhere; it’s a permanent, high-impact part of the fragrance story.

Take care of yourselves and your noses.

References and Further Reading

For those eager to delve deeper into the world of perfumery, here are some resources for further exploration:

Books:

- Chemistry and the Sense of Smell by Charles S. Sell

- Fundamentals of Fragrance Chemistry by Charles S. Sell

- Chemical Bonds.An Introduction to Atomic and Molecular Structure by Harry B. Gray

Scientific Papers, Journals and Blog Posts:

- Amine – Wikipedia, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Origin and history of amine

- Amine Structure, Properties & Examples

- Nomenclature of Amines

- Amines – Structure and Naming

- Schiff Bases — A Primer – Perfumer & Flavorist

- Advanced IUPAC Nomenclature XI

- Characterization and Sensory Properties of Volatile Nitrogen Compounds from Natural Isolates

How do amines affect fragrance scent profiles?

mines are the “modifiers” that bring realism. Without them, your jasmine is just a flat, synthetic sweetness—it lacks the “bloom.” Amines provide the animalic, earthy, and roasted nuances that make a scent feel three-dimensional. They can take a fragrance from “clean and boring” to “narcotic and alive.” Just remember the concentration rule: at 100%, they’re a biohazard to your nose; at 0.01%, they’re pure magic.

Which amines are most commonly used in perfumes?

If you’re looking at a professional formula, you’re mostly going to see Indole and Methyl Anthranilate. Indole is the heart of white florals. Beyond those, you’ll see Quinolines (like IBQ) for that rugged leather scent and Pyrazines for anything that needs to smell toasted, like coffee or chocolate. These are the workhorses of the nitrogen family.

Are amines safe for skin and fragrance stability?

Generally, yes, but they come with a “handling manual.” Most amines used in perfumery are safe at the trace levels we use, but you have to watch the IFRA standards. For example, Methyl-N-methylanthranilate is phototoxic, so we’re capped at 0.1% in leave-on products. As for stability, they are reactive. They will change the color of your juice and can be deactivated by acidic environments. You don’t just “set and forget” an amine; you manage it.

How do esters compare to amines in aroma characteristics?

Esters are the “nice guys”—they usually give you those easy, fruity, and clear floral notes (think of the pear scent in Benzyl Acetate). Amines are the “eccentrics.” While esters are generally light and pretty, amines bring the weight, the grit, and the animalic “funk.” If esters provide the melody of a fragrance, amines provide the bassline—you might not always pick it out individually, but the whole track feels empty without it.

How is aurantiol synthesized for perfume use?

In the fragrance industry, Aurantiol isn’t just “mixed”—it’s synthesized through a controlled condensation reaction. We take Methyl Anthranilate (the amine) and Hydroxycitronellal (the aldehyde) and combine them, usually in a 1:1 molar ratio.

To get the reaction to go to completion, we apply gentle heat—typically around 90°C to 100°C. As the molecules bond to form the Schiff base, they release water (H2O) as a byproduct. In a professional setup, we often perform this under a slight vacuum to “pull” the water out, which shifts the chemical equilibrium and ensures we get a high-quality, stable yellow Schiff base.

Which aldehydes pair best with methyl anthranilate?

While Hydroxycitronellal is the classic partner for creating Aurantiol, Methyl Anthranilate is a versatile player. Here are the top-tier pairings:

–Hydroxycitronellal: Creates Aurantiol. The industry standard for sweet, muguet (Lily of the Valley), and orange blossom notes.

–Lilial: Creates Liliunthial. This gives you a fresher, more watery, and sophisticated floral profile compared to the heavy sweetness of Aurantiol.

–Triplal: If you want a “Green Anthranilate,” this is it. It results in a sharp, grassy, and floral Schiff base that works wonders in gardenia accords.

–Decanal (Aldehyde C-10): This pairing leans heavily into the citrus-zest territory, reinforcing orange peel notes while adding massive tenacity.

Why did my perfume turn dark purple/brown?

This is almost always an unintended Schiff Base reaction or Indole oxidation. For example, mixing Methyl Anthranilate (amine) with Vanillin (aldehyde) creates a deep orange-to-brown shift, while Citral can turn it almost black.